02:11. The room is empty the way a room gets empty after everyone decides the day is over. One chair. One laptop. A dashboard that looks confident but has earned none of it. The numbers sit there like they’ve never lied before.

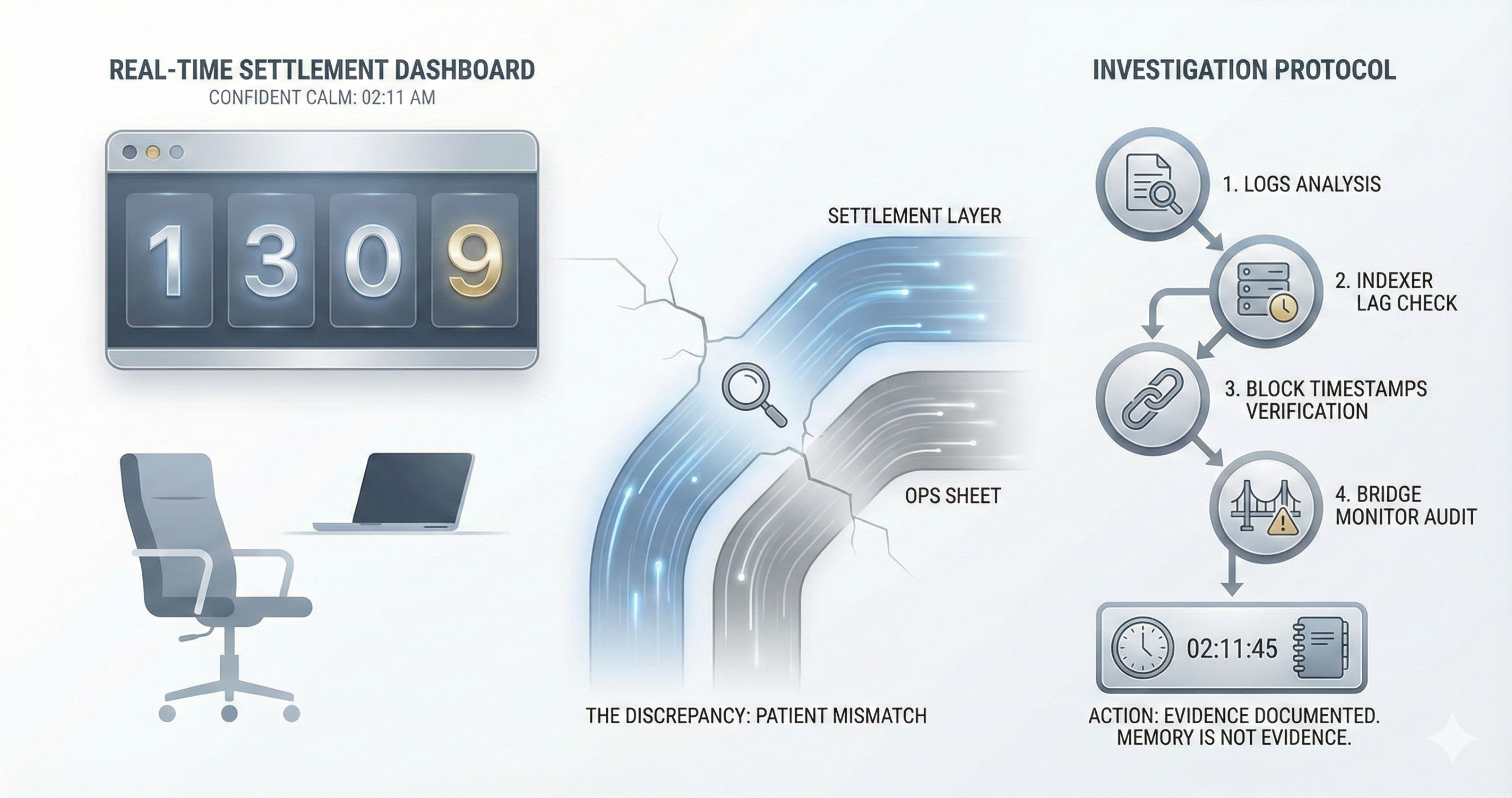

There’s a small discrepancy. A hairline crack between what the settlement layer says is final and what our ops sheet says should be final. Not enough to wake the on-call rotation. Enough to keep me awake anyway. The kind of mismatch that doesn’t scream. It just stands there, patient, waiting for you to look away.

I’ve learned to distrust calm screens. Calm is often just “we haven’t measured the right thing yet.” I open the logs. I check the indexer lag. I check the block timestamps. I check the bridge monitor because bridges have a special talent for failing in ways that look like everybody else’s fault. I write down the exact time because memory is not evidence.

Slogans don’t show up in this room. They never do. They stay outside, on landing pages and decks and group chats. In here, the only thing that matters is whether money arrives when it’s supposed to arrive. Not “money” as a concept. Payroll. Vendor invoices. Refunds. Client contracts with clauses that don’t care how elegant your architecture is.

People say “transparency” like it’s always good. Like more light is always better. It isn’t. “Public” is not the same as “provable.” Public can mean anyone can see it. Provable means you can demonstrate validity under rules, with evidence that survives an audit. And in the adult world, audits are not a vibe check. They’re a legal process.

Privacy is not always a preference either. Sometimes it’s a duty. Sometimes you’re required to keep things confidential: salaries, client positioning, trading intent, sensitive commercial terms. You don’t get to shrug and say, “It’s on-chain, what can we do?” Because “what we can do” is the whole job.

That’s why I like the sealed-folder metaphor. In the audit room, you don’t dump every document into the hallway to prove you have nothing to hide. You keep a sealed folder on the table. Everyone can see it exists. Everyone can see when it was created. Everyone can see the seal. But only authorized parties can open it—auditors, regulators, compliance—under controlled procedure. The seal tells you if something changed. The access log tells you who looked, and when.

That’s the balance we actually need: selective disclosure for the right people, at the right time, without turning every private fact into public entertainment.

This is where Phoenix private transactions fit, not as a magic trick, but as discipline. Confidentiality with enforcement. The network can still enforce the rules—validity, authorization, no double-spends—without leaking every detail to the world. Proof without gossip. Verification without exposure. You can show that something is correct without publishing the whole story.

Because indiscriminate transparency causes real harm. Not theoretical harm. Practical harm. If a client’s strategy is visible, competitors can position against them. If salary flows are visible, you create social and physical risk for employees. If trading intent is visible, you create market conduct problems and front-running pressure. Even when nothing illegal happens, the public record can distort behavior, and distorted behavior becomes operational risk.

The discrepancy on my screen is still there. It hasn’t moved. That’s information too. I stop trusting my assumptions and start working the chain of custody.

Vanar’s design—at least the way I think about it at 02:11—is a containment strategy. Modular execution environments over a conservative settlement layer. The settlement layer should be boring. Dependable. Predictable. The part you don’t brag about because bragging usually means you changed it too much.

Separation is containment. If something misbehaves in an execution environment, you want the blast radius to stay inside that boundary. If a product layer gets complicated—and it will, because you’re dealing with games, entertainment, brands, consumers—you don’t want that complexity to infect finality itself.

That mindset is also why EVM compatibility matters in operations. Not as a marketing badge. As fewer surprises. Familiar tooling. Familiar assumptions. A smaller pile of weird edge cases that only exist because you decided to be different for the sake of being different. The fewer bespoke components you invent, the fewer bespoke disasters you have to debug.

Then there’s consensus. Hybrid consensus is not a philosophical statement. It’s a failure model. It’s a way of saying: we want defined validator behavior and accountability while the system grows into the kind of network real users and real businesses can rely on. In early stages, having a clear validator set and reputation-based onboarding can be less romantic, but more legible. Legible systems are easier to secure because you can actually name the responsibilities.

Community staking is the other half of that. Not as “support the token.” As bonding. Skin-in-the-game that functions like a security deposit. When you stake, you’re not just chasing yield; you’re underwriting behavior. You’re helping decide which validators deserve weight, and you’re accepting that accountability has a cost.

That’s how I try to frame $VANRY in my head: responsibility. Fees are the obvious part. Staking is the adult part. A bond tied to performance and honesty. A mechanism that turns “trust us” into “we can be penalized.”

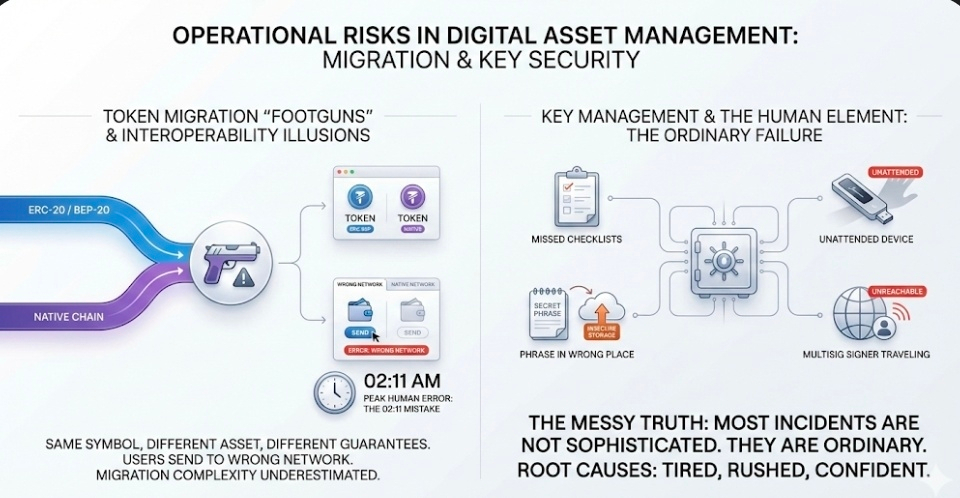

But the sharp edges don’t care about philosophy. They care about bridges, migrations, and humans.

ERC-20 and BEP-20 to native migrations are not just “interoperability.” They’re footguns with good documentation. The same symbol in a wallet can be a different asset with a different set of guarantees. Users send to the wrong network. Teams schedule migrations and underestimate how many people will copy the wrong address from the wrong tab at the wrong time. Someone will always do it at 02:11, because that’s when humans do their most creative mistakes.

Key management is worse. Human error is worse. Missed checklists. A signing device left unattended. A phrase stored in the wrong place “just for a minute.” A multisig signer traveling and not reachable when you need them. The messy truth is that most security incidents are not sophisticated. They are ordinary. They happen because a person got tired, or rushed, or confident.

Trust doesn’t degrade politely. It snaps. And when it snaps, it snaps in the places where the adult world cares: the audit room and the room where someone signs under risk.

By 03:18 the discrepancy resolves into something that makes sense. The chain is fine. The indexer is behind. The dashboard is calm again, which proves nothing. I write the incident note anyway because the habit matters more than the drama.

By 03:41 I update the runbook with the line that should have been there from the beginning: assume the dashboard is wrong until you can prove it’s right. Not because dashboards are evil. Because the cost of blind trust is never paid by the dashboard.

And by 04:02, when the building is still quiet and the world is still asleep, I’m thinking about what “adoption” actually means. It means permissions. Controls. Revocation. Recovery. It means compliance obligations you cannot hand-wave away. It means selective disclosure that doesn’t leak, and auditability that doesn’t break.

It means the sealed folder stays sealed until it’s supposed to open.

It means the settlement layer stays boring even when everything on top of it is loud.

It means staking is not fan behavior. It’s a bond.

And it means there are only two rooms that matter in the end. The audit room, where proof has to survive scrutiny. And the other room, where a human being signs a document, takes on risk, and expects the system beneath their signature to be dependable—especially at 02:11, when nobody is watching and everything that’s fragile starts to show.