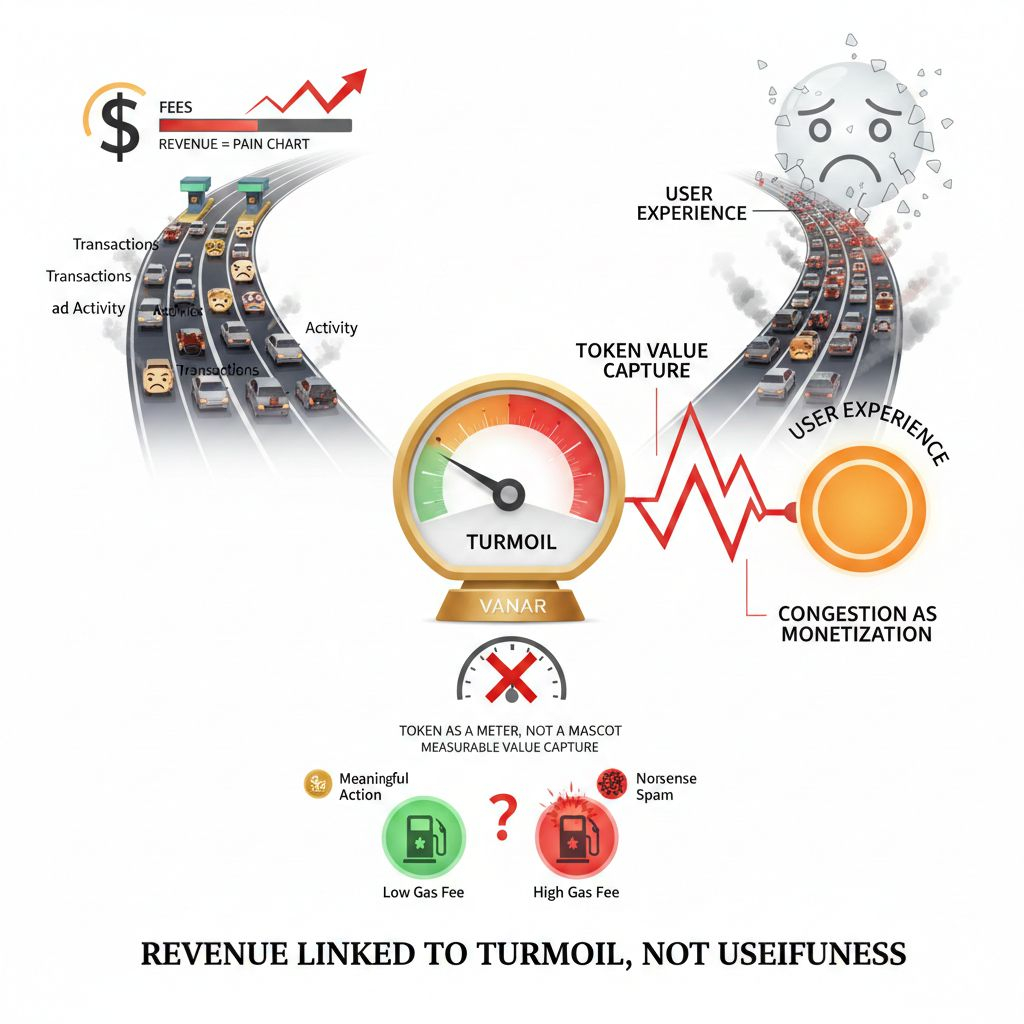

I still remember the first time I tried to convince myself that a chain “making money” meant it was becoming a real business. The dashboard looked great—transactions climbing, activity charts glowing, fees ticking up in a way that made everyone feel like we’d finally found the magic formula. In that moment it felt almost comforting, like the market was handing us a clean, measurable signal that the thing was working. But then I actually used the network during a busy stretch, and the emotional logic of the numbers collapsed fast. The chain wasn’t earning because it was creating more value for users. It was earning because it was getting worse to use. The “revenue” line was basically a pain chart, and the product story depended on the user experience degrading at the exact moment you’re supposed to be proud of demand.

That’s the part I can’t unsee anymore, and it quietly poisons the way I look at most Layer-1 narratives. Most Layer-1 tokens are commodity-constructed but sold as businesses: the token is treated like a barrel of oil, yet marketed like equity in a growing company. People will point to “users” and “activity” and “ecosystem adoption” as if the token automatically captures that upside, but it doesn’t—at least not in any honest, repeatable way. The token captures upside only when the network is pushed toward full capacity, when blockspace becomes scarce, when things start to feel cramped. It’s like calling traffic jams a business model for a highway. Your product generates money when it malfunctions, and the more people want to use it, the more it punishes them. That is one of the worst business models you could ever design: congestion as monetization, turmoil as margin, user suffering as a growth lever.

The default crypto idea of monetization is so familiar now that people barely question it. You sell blockspace. You let demand bid up gas. You treat the fee market as “revenue.” And yes, gas does its job as a spam filter and a congestion control mechanism. But gas is a terrible proxy for real value creation, and it becomes obvious the moment you stop looking at aggregate charts and start looking at what’s actually happening. A genuinely meaningful action can cost the same as nonsense spam. A high-integrity verification event can be priced like a pointless click. A user doing something that creates real economic or social value might pay the same toll as someone who’s simply flooding the network with meaningless activity. The chain can’t distinguish value from noise, so it charges a toll that often has nothing to do with what the user actually accomplished. Then, when demand spikes, the chain earns more precisely when users are having the worst experience. Revenue becomes linked to turmoil, not usefulness. The network “wins” by becoming less usable.

That is why Vanar has been sitting in my head lately, because it keeps hinting at an instinct that doesn’t need congestion to work. The design language around Vanar reads like it’s trying to make the base layer intentionally boring: predictable, stable, something you can build on without feeling like you’re renting execution from a volatile auction. Their architecture speaks in the direction of fixed-fee targets—anchoring transactions to a predictable value rather than letting the user experience swing wildly with token price or sudden demand. That alone is already a quiet rejection of the standard playbook, because it suggests the network isn’t relying on volatile gas pricing as its long-term business model. It’s almost like Vanar is saying: we don’t want to get paid more when things are painful; we want the baseline to be smooth enough that you stop thinking about it.

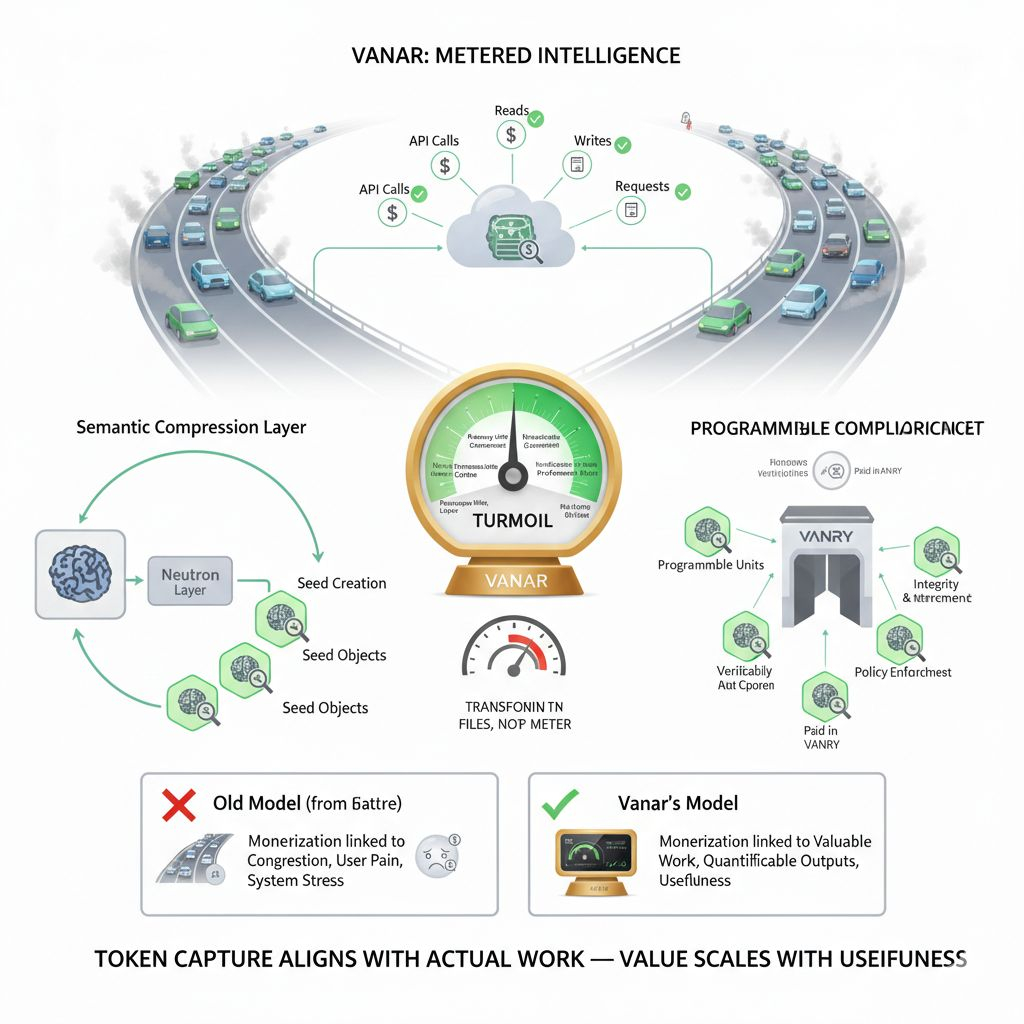

But the bigger move, the one that actually shifts the entire thesis, is what comes after that baseline: the idea that the chain’s real monetization is not blockspace or even gas, but high-value actions—metered intelligence. The way I keep translating it in my mind is simple: cloud platforms don’t get rich because servers get congested. They get rich because they can meter outcomes—API calls, reads, writes, requests—things that are countable and directly tied to what customers experience as value. You don’t pay a cloud provider because you enjoy their service being overloaded; you pay because you can measure what you’re consuming and you can defend that consumption as meaningful work. Vanar appears to be chasing a similar shape, where the token becomes less like a generic toll and more like a cloud billing meter—billing intelligence through a model closer to API calls, but not for raw blockspace. For memory. For verification. For reasoning. For the kind of outputs that a real application or an enterprise workflow can point at and say, “this is what we got.”

And this is where the gas model’s limitations become painfully clear by contrast. Gas isn’t value-aware. It can’t price a valuable action differently than a useless one. It charges based on computational effort and scarcity of execution space, not the economic meaning of what just happened. Vanar’s thesis, as I read it, tries to restructure that relationship. Instead of linking monetization to congestion, it links monetization to services that are naturally countable and naturally defensible—services that have quantifiable outputs. It’s a more advanced thesis than most crypto narratives because it doesn’t require the chain to be “maxed out” to make the token story coherent. It requires the chain to provide billable outputs that scale with actual usefulness.

Neutron is the piece that makes this shift feel concrete rather than rhetorical, because it directly attacks the “blob problem”—the way most systems treat data as something inert. In most stacks, data is a file sitting somewhere, maybe with a hash, maybe with metadata, maybe with a pointer, but functionally it’s a blob until you pull it back into an application and do the real work off-chain. Vanar’s Neutron layer is described as a semantic compression layer that restructures large files into smaller, verifiable Seed objects—Seeds designed to fit agents and applications, not just storage systems. This is not presented as “we store files.” It’s presented as “we transform files.” And the emphasis is important: not compression that only preserves bytes, but semantic compression that preserves meaning. The central argument is that you can keep the meaning intact while creating something compact and structured enough that an AI agent can query the Seed without having to recreate the original file. In other words, you don’t drag the whole document around every time; you work with a representation that’s small enough to be usable but still verifiable enough to trust.

I keep thinking about the word “aggressive” in how you framed Neutron, because it captures what’s unusual here. Vanar isn’t trying to politely join the existing storage narrative. It’s aggressive in placement: it’s not “store files,” it’s “restructure files into programmable Seeds.” That implies a different economic surface. If the thing you create is not a dead blob but a programmable unit, then it becomes something you can meter. Seed creation becomes a billable event. Seed verification becomes a billable event. Seed updates, anchoring, proofs, queries—these become discrete service actions rather than vague “gas consumption.” That’s how you turn a token into a billing meter. You stop charging for abstract execution and start charging for clearly defined outputs.

Once you have Seeds as structured, verifiable units, the idea of metered intelligence stops being vague and starts looking like an actual business model. In a cloud world, you don’t pay for the philosophical concept of compute. You pay for the calls, the reads, the writes—the moments where a system did something measurable. Vanar’s angle looks like it’s trying to build that kind of measurability into blockchain-native primitives. If Neutron makes data workable by the chain—if it turns data into something agents can query and verify—then the chain is no longer just a settlement layer with a fee market. It becomes a service surface where actions have a price and a reason.

And then there’s the next implied layer of monetization: programmable compliance and verification as a service, priced in VANRY rather than hidden behind volatile gas. This is where I think the story becomes genuinely dangerous—in a good way—because compliance is not a crypto-native category, it’s a real-world budget category. Enterprises already pay for audit trails, integrity checks, verification workflows, document authenticity, policy enforcement, and all the boring machinery that keeps organizations legally sane. If Vanar can take those actions—verification, reasoning, compliance triggers—and make them programmable, verifiable, and meterable, then the token’s role becomes less speculative and more consumptive. You pay because a service was delivered. You pay because a check was performed. You pay because reasoning was applied to data that matters. That’s not “gas revenue.” That’s a service economy.

Vanar still has set transaction charges to build on, and that matters because it gives the network a baseline fee model. But the second level of monetization you’re pointing to is the long-term change: metered intelligence. It’s the difference between “the chain earns when blockspace demand peaks” and “the chain earns when valuable work is performed.” It breaks the old dependency where the token needs congestion to justify itself. It flips the incentives so that the chain can remain smooth and still grow economically—because the monetization is tied to high-value actions, not system stress.

I’m not pretending this is easy, and I’m not dressing it up as guaranteed. Turning “meaning” into a reliable primitive is hard. Turning “reasoning” into something enterprises trust is harder. Designing a pricing surface that developers accept as fair, predictable, and worth paying is a real challenge. And any time a project puts AI language near a chain narrative, it risks sounding like every other vague promise in the market. But even with all that skepticism intact, I can’t ignore how refreshing it is to see a model that doesn’t treat user pain as profit. The gas model has trained the industry to celebrate moments when users suffer. Vanar’s direction, as described here, is an attempt to make the token capture align with actual work—memory, verification, reasoning—so value capture scales with usefulness rather than congestion.

If they execute, it won’t look like a typical crypto win, and that’s the point. It won’t be loud. It won’t be “fees are up because the chain is jammed.” It will be the quieter kind of success that cloud platforms have mastered: people pay because the output is measurable, because the service is reliable, because the billing makes sense, and because the work being done is high-value enough that metering it feels natural. That’s the shift I’m following, and it’s the first time in a while I’ve seen a token thesis that doesn’t secretly rely on the network breaking under its own demand to look like a business.