A while ago, issues related to Greenland led to friction between the United States and Europe, and the cooperation between Canada and China has also caused friction between the U.S. and Canada. The biggest variable in the U.S.-China market throughout 2025 is the trade dispute and the redistribution of supply chains.

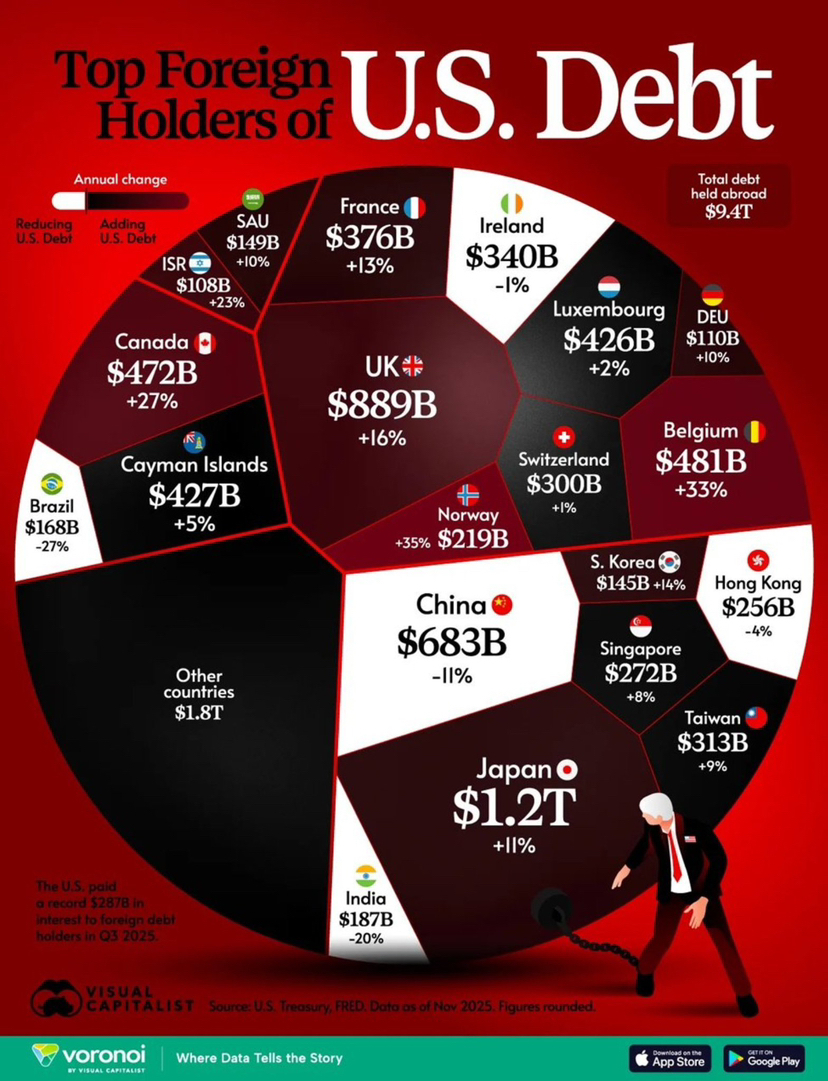

However, from the perspective of U.S. Treasury purchases, overseas entities hold a total of 9.4 trillion U.S. dollars in Treasury bonds, of which Europe (not the EU) accounts for 33.4%. Japan is one of the largest holders among single countries and continues to increase its holdings, indicating that geopolitical conflicts can tear narratives apart, but it is difficult to immediately disrupt the settlement and collateral systems.

First, the more conflicts there are, the more U.S. dollar assets resemble cash during wartime.

Geopolitical conflicts bring uncertainty in energy and shipping costs, increased risks of supply chain disruptions, and extreme policies (including sanctions, export controls, industry subsidies, and defense budget expansions, etc.). This will directly push up risk premiums, causing global funds to naturally tend to return to U.S. dollar liquidity + U.S. Treasury collateral.

Thus, the overseas U.S. Treasury holdings that can be seen actually reflect the distinction between 'friends and foes,' displaying more obvious custody and allocation characteristics in the structure of 'financial centers and allied systems.'

Second, high European holdings are precisely the result of the financialization of conflict.

Europe, especially countries like the UK, Luxembourg, Ireland, and Belgium, often do not love the U.S. more than others, but global funds rely more on mature custody, clearing, repurchase, and derivative systems in a conflict environment. These systems most easily record positions in European financial hubs.

In plain language, the more chaotic the world becomes, the more funds need channels; Europe is the channel, and the U.S. provides the underlying assets. This is why we see such a high proportion of U.S. Treasuries held by Europe, reflecting financial infrastructure and funding pathways rather than emotional statements.

Third, Japan is a passive major player under geopolitical conflict.

For Japan, geopolitical conflicts will amplify two types of pressure:

A. Exchange rate pressure and energy price pressure. The more volatile the exchange rate, the more foreign exchange assets are needed for buffering.

B. The higher the risk, the more life insurance or pension funds need duration assets to match liabilities. Coupled with the need for foreign exchange intervention when necessary, Japan's stance on U.S. Treasuries resembles a structural allocation; it's not about whether they want to buy, but the system must hold them.

This also explains why, during rising tensions and conflicts, Japan often does not publicly take sides like a slogan but continues to maintain a stable weight of U.S. dollar assets on the asset side.

Fourth, China's logic of reducing holdings is essentially a reflection of geopolitical conflict logic.

An increase in conflict means a rise in tail risk. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has already taught us a good lesson; risks of freezing, sanctions, payment channel risks, and even the politicization of assets will accompany conflicts.

Therefore, China's reduction in holdings resembles risk management of foreign reserves, lowering single counterparty risk exposure, increasing asset mobility, and enhancing diversification. Of course, reducing holdings does not mean decoupling, nor does it mean exiting the U.S. dollar system, because in reality, there are not many deeply liquid assets that can be replaced in the short term. This is a love-hate relationship; politically, there is an escalation of confrontation, yet financially, they are still constrained by the same system.

Geopolitical conflicts will accelerate the contradictions in finance, interest rates, and debt.

Conflicts mean rising defense spending, industry subsidies, and costs of localizing supply chains, all of which will ultimately fall on fiscal deficits. The larger the deficit and the higher the interest rates, the more interest payments on U.S. Treasuries resemble an ever-expanding black hole.

The more conflicts there are, the more U.S. Treasuries are needed, and the higher the interest costs borne by the U.S., the higher the costs, the easier it is for policies to be backfired by the market. This is the real financial battleground in the coming years; by 2025, the interest the U.S. pays to other countries will reach $287 billion.

From the distribution of funds, the so-called 'friends and foes' are actually very clear at the financial level. The U.S., European financial hubs, and Japan will naturally 'band together' within the same settlement and collateral system, not because they are more united, but because they share the same pool of U.S. dollar assets, custody and clearing networks, repurchase markets, and risk hedging tools. The more chaotic the world becomes, the more this system needs stable underlying collateral; U.S. Treasuries become more like standard ammunition for wartime cash.

Although China is reducing its holdings, it remains one of the largest holders of U.S. Treasuries. This fact itself illustrates that the confrontation between China and the U.S. can escalate in narrative but has not yet fully translated into a financial rift, at least not to the point of liquidation. More realistically, it's not that they don't want to tear the façade; it's that there are too few deeply liquid assets that can be replaced in the short term, and foreign reserve management cannot be based on emotions.

You can dislike your opponent, but it's very difficult to operate without your opponent's system in the short term.

PS: This situation also occurs in the cryptocurrency field; you can criticize #Binance every day, but when you choose to trade, you might still have to choose Binance, not because you like it, but because depth and liquidity often leave you with no other options.