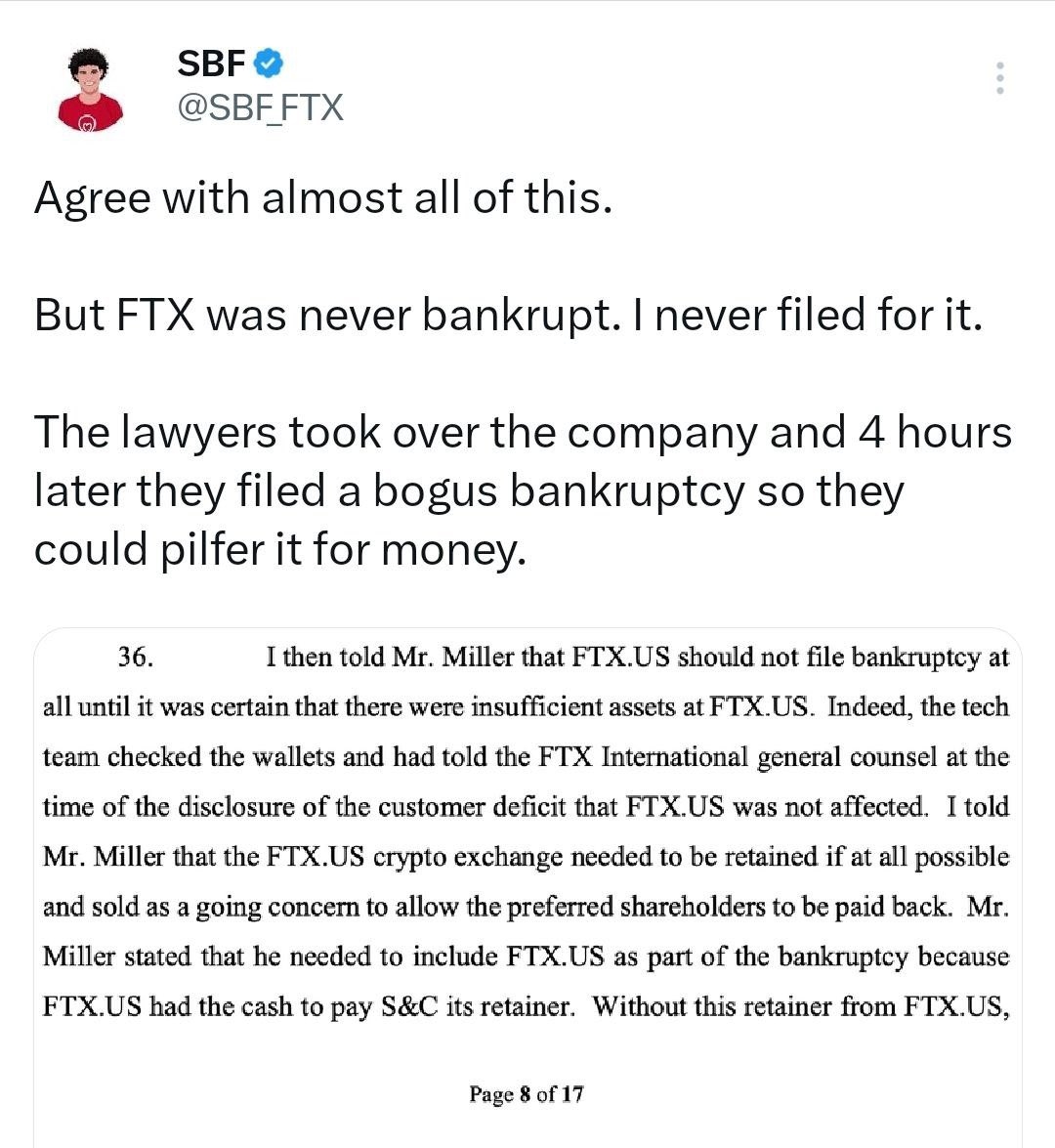

When Sam Bankman-Fried says that FTX was “never bankrupt” and that lawyers filed a “bogus” bankruptcy to take its money, it immediately grabs attention. Not because the claim is new — but because of what it forces us to examine.

This isn’t just about SBF defending himself.

It’s about understanding how bankruptcy works, how corporate control shifts in crises, and how narratives get rewritten after the fact.

Whether his claim is true or not, it carries serious educational value for anyone operating in markets, startups, or crypto.

SBF’s argument is essentially this: FTX, according to him, still had assets, still had a functioning business, and still had a path to recovery. The collapse, in his view, was not insolvency — it was a liquidity crisis made worse by panic, withdrawals, and what he calls an unnecessary bankruptcy filing.

He claims that once bankruptcy lawyers took control, the company was frozen, value was destroyed, and assets were drained through fees and restructuring — not saved.

That’s a serious accusation, and it forces a key distinction most people don’t fully understand.

Insolvency vs. Illiquidity A Critical Lesson

A company can fail in two very different ways.

Insolvency means liabilities exceed assets.

Illiquidity means assets exist, but can’t be accessed quickly enough to meet obligations.

SBF is arguing FTX was the second, not the first.

This distinction matters because bankruptcy law does not require absolute insolvency. If a company cannot meet its obligations when due especially during a run bankruptcy can legally be triggered. In traditional finance, many firms have collapsed this way. Banks, funds, and exchanges can look healthy on paper yet still implode if confidence disappears.

That’s the first educational takeaway: markets don’t wait for accounting clarity. They react to trust.

Here’s the part most people miss. Once a bankruptcy filing happens, control shifts from founders to court-appointed administrators. Operations slow or stop. Assets are frozen. Every decision becomes legal, not strategic.

The goal changes from saving the business to maximizing recoveries under law. That often means selling assets slowly, prioritizing legal process over speed, and incurring massive professional fees. From SBF’s perspective, this is where value was destroyed. From the court’s perspective, this is how you ensure fairness.

Neither view is irrational — they just serve different incentives.

Even if FTX had assets, that does not automatically absolve leadership. The core question has never been whether FTX had assets somewhere. The real questions are whether customer funds were segregated, whether liabilities were accurately disclosed, whether risk was controlled or hidden, and whether withdrawals could be honored without deception.

Bankruptcy often reveals structure, not just balance sheets. FTX didn’t collapse because of one bad day. It collapsed because trust evaporated instantly — and trust evaporates fastest when transparency is missing.

That’s the second lesson: in finance, opacity is leverage — until it becomes a weapon against you.

Calling the bankruptcy “bogus” and accusing lawyers of draining value fits a common post-collapse narrative. It appears in corporate failures, hedge fund blowups, and startup implosions. Founders often believe they could have fixed things if given time. Lawyers believe time increases damage.

Both may be partially right. But courts almost always side with process over promises — especially when billions in customer funds are involved. That’s not personal. It’s institutional risk management.

This situation highlights something critical for crypto’s future. Centralized platforms live and die by governance, not technology. FTX didn’t fail because blockchains broke. It failed because centralized control met opaque risk.

And when centralized firms fail, they fall under traditional legal systems — not crypto ideals. Bankruptcy courts decide outcomes. Lawyers replace founders. Time destroys optionality. Crypto doesn’t escape old rules just because the assets are digital.

Even if FTX could theoretically recover value over time, bankruptcy is not just about net worth — it’s about credibility, access, and control. Once customers can’t withdraw, counterparties stop trusting you, and information is unclear, the market has already passed judgment.

That’s when bankruptcy becomes inevitable — not as punishment, but as containment.

The hardest truth this claim exposes is simple: companies don’t collapse when assets disappear. They collapse when trust does. Bankruptcy is rarely the cause of destruction. It’s usually the formal recognition that destruction already occurred.

Whether or not FTX was technically solvent at some point matters far less than this reality. Once confidence was gone, the business was already finished.

For builders, investors, and users, the lesson is simple but brutal.

Transparency beats complexity.

Liquidity beats valuation.

Trust beats everything.

And once trust breaks, no balance sheet — real or imagined — can save you.