The office is not really an office anymore. It’s a room with a desk, a chair that remembers every long night, and a screen that pretends it can explain the world. The air is cold in that way that makes you feel observed. One person sits alone, sleeves pushed up, eyes dry, watching a dashboard nobody trusts. We keep it open because it’s faster than digging through raw logs, but we don’t believe it. We believe in reconciliations. We believe in ugly truth.

A discrepancy blinks in the corner. Small. A rounding error. A delay. A tiny mismatch between what the system says was executed and what the system says was settled. It shouldn’t matter. It does. Not because it will bankrupt anyone, but because it threatens sleep. Because tiny mismatches are how real incidents introduce themselves—polite at the door, then inside the house, then living there.

So we start the incident the way adults start things: with facts, not feelings. Time, scope, impact. What we observed. What we expected. What we changed in response. The words are tight because loose words become excuses, and excuses become culture. Culture becomes risk.

Somewhere outside this room, the slogans still exist. People say “transparent” like it’s a moral position. People say “public” like it automatically means “proven.” In here, those words split apart. Public is not the same as provable. Visible is not the same as auditable. A transaction hash can tell you that something happened, but it won’t tell you whether it happened within policy, with the right approvals, under the right constraints, for the right reasons. It won’t tell you whether someone had authority or just had access. In the real world, authority matters more.

This is the point where the conversation usually turns childish. The moment you say privacy, someone hears secrecy. The moment you say selective disclosure, someone hears loophole. But privacy, in the places where payroll runs and contracts get signed, is often not a preference. It’s a legal duty. It’s written into agreements with clients. It’s written into labor law. It’s written into what you are allowed to reveal and what you must protect.

Auditability is the opposite kind of duty. Not optional. Not negotiable. If you take money from clients, if you move funds for partners, if you operate inside regulated lines, you will be asked to prove what happened. And you will not be asked gently. You will be asked by people whose job is to doubt you.

This is where I always end up thinking about the audit room. Not as a metaphor for drama, but as a place with a smell—paper, toner, coffee gone stale. The audit room is where you bring a sealed folder. You do not dump the contents of your company onto the street and call that integrity. You bring what’s required, you document chain-of-custody, you show the evidence to authorized parties, you answer questions, you let them verify. You reveal enough to prove, but not enough to harm.

Selective disclosure isn’t soft. It’s disciplined. It is the difference between “we won’t tell you anything” and “we will tell everyone everything.” Both extremes are irresponsible. The sealed folder is the adult middle.

If you translate that into an onchain world, the goal becomes clear: proof without broadcast. Verification without public exposure. The ability to demonstrate that a transaction is valid, compliant, and authorized—without exposing the details that create collateral damage.

That’s why private transactions matter when they’re designed correctly. Not as magic invisibility. Not as a cloak for bad behavior. As confidentiality with enforcement. Validity proofs that let the network enforce rules without leaking the private parts. The system can still reject what is invalid. It can still enforce constraints. It can still be audited. It just doesn’t turn every sensitive business detail into permanent public intelligence.

Because indiscriminate transparency hurts people. It hurts businesses in boring, predictable ways. It shows client positioning. It shows supplier terms. It shows salary flows. It shows trading intent. It tells competitors what you’re doing before you can do it. It can create market conduct problems without anyone even trying. And when people know they will be exposed, they stop using the system for anything that matters. They move to side channels. They build shadow ledgers. The chain stays “transparent,” and the truth quietly walks away.

So the technical design starts to feel less like ideology and more like containment.

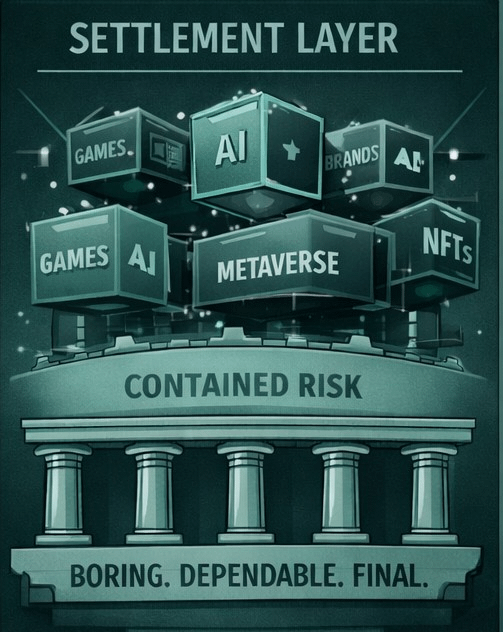

Vanar’s architecture—modular execution environments on top of a conservative settlement layer—reads like someone has been in this room before. It says: let settlement be boring. Let it be dependable. Let it do the final accounting and do it the same way, every day, under stress, for years. Put complexity where it can be isolated. Put experimentation where it can be contained. Separation isn’t aesthetics. Separation is how you keep one failure from becoming everybody’s failure.

Execution environments can evolve. They can serve different mainstream verticals—games, entertainment, brands, AI, metaverse experiences—without forcing the base layer to carry every new risk. The settlement layer should not be a place where you discover surprises. Settlement should be the part of the system that makes people breathe slower.

And EVM compatibility, framed honestly, is not about being trendy. It’s about fewer surprises. Fewer unknown unknowns. Tools that already exist. Auditors who already understand what they’re looking at. Developers who have already learned, painfully, how not to repeat certain mistakes. You don’t eliminate risk with compatibility. You reduce the novelty tax. At novelty is expensive.

Now, about $VANRY.

This is where it’s easy to turn shallow. People want price talk. People want prophecy. But in an incident room, tokens are not wish objects. They are responsibility objects. If a network uses staking, staking is not a cheer. It is a bond. It is a way to attach consequences to behavior. It says: if you participate in securing and operating this system, you post collateral. If you break the rules, the collateral is at risk. This is not romance. It is accountability expressed in math.

Optional verification, done right, can change what kind of activity can safely move onchain. Not because it’s exciting, but because it’s practical. If a business can prove compliance without leaking sensitive details, it can move real processes onchain—processes it would never expose publicly. Payroll-adjacent flows. Client billing logic. Vendor payments. B2B agreements. Things that require audit trails and also require discretion. If those processes can exist onchain without causing harm, then the chain becomes more than a stage. It becomes infrastructure.

And infrastructure creates demand in an unglamorous way: through obligation. Through use. Through systems that must run because the real world is attached to them.

But the sharp edges don’t soften just because the architecture is clean.

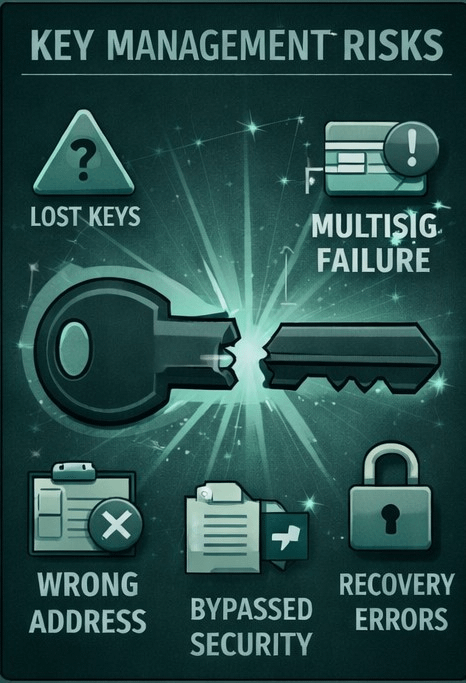

Bridges and migrations are where certainty goes to get injured. ERC-20 and BEP-20 representations moving to a native asset sounds tidy on paper. In practice, it’s a corridor full of doors, and every door has a person holding a key. Finality assumptions. Confirmation counts. Event parsing. Timeouts. Manual interventions. One mistaken setting, one wrong chain ID, one copy-pasted address from a compromised clipboard, and you have an incident that doesn’t care how good your philosophy is.

Key management is not a technical footnote. It’s where most “trust” actually lives. Keys get lost. Keys get shared incorrectly. Seeds get stored in the wrong place. Multi-sig policies get bypassed because someone is rushing. Recovery plans exist in documents that nobody reads until they’re desperate, and then it’s too late. Human error is not a rare event; it’s the default weather.

And trust doesn’t degrade politely. It snaps.

It snaps when someone skips a checklist. It snaps when a rotation isn’t logged. It snaps when a signer changes and nobody updates monitoring thresholds. It snaps when the dashboard says green and reality says gray. Then the same organization that once used the system smoothly turns into a room full of screenshots and suspicion. Not because people become irrational, but because they become responsible. They stop believing and start demanding evidence.

Which brings us back to the sealed folder.

In a mature onchain system, you want the ability to keep things private by default where privacy is duty, and provable on demand where proof is duty. You want permissions, controls, revocation, recovery. You want a clean way to authorize access without turning access into a permanent leak. You want compliance obligations to be satisfied without turning every sensitive detail into permanent public harm.

“Optional verification” is not a loophole if it’s built like an audit room. It is a way to make public networks usable for adult workflows. It is a way to stop confusing “public” with “provable.” It’s a way to carry sealed folders through open space.

By the end of the report, the language shifts. It always does. Not because we intend poetry, but because humans live inside systems. We pretend we are writing about transactions, but we are writing about responsibility. We are writing about the kind of world where someone signs their name under risk.

There are two rooms that matter.

The audit room, where evidence is opened under authority and examined without mercy.

And the other room, quieter, where someone signs approvals, authorizes payments, accepts liability, and knows the system will either protect them or betray them.

If Vanar wants real-world adoption, it has to serve both rooms. It has to let privacy be a duty without turning it into darkness. It has to make auditability non-negotiable without making exposure compulsory. It has to make settlement boring and dependable, and keep complexity contained where it can be understood and controlled.

And it has to earn trust the hard way: not through slogans, but through proof that survives