If you have spent any time using crypto apps, you know the weird part is not the technology, it is the feeling. One day a simple action costs almost nothing, the next day it costs enough to make you hesitate. Sometimes things confirm quickly, sometimes you stare at a spinner and wonder if you broke something. For most people, that is not a fun learning curve, it is a reason to leave and never come back. That is the background problem Vanar is trying to treat as the main problem, not as a side issue.

Vanar is a Layer 1 blockchain that is built around the idea that real adoption will come from consumer style products, not from endless new finance tools. The team talks a lot about games, entertainment, and brands, and you can see that direction in the way the network is framed. Instead of positioning itself as a chain for advanced users, it aims to be a chain that developers can hide behind good product design, so the user experience feels closer to a normal app.

That sounds simple, but it forces different priorities. A chain that mainly serves traders can live with unpredictable fees and a steep learning curve, because the users are motivated enough to put up with it. A chain that wants millions of everyday users cannot. Games and mainstream apps survive on repetition, people doing small actions over and over, sometimes many times a day. That only works when the experience is predictable and the cost per action is stable enough that neither the user nor the developer has to constantly think about it. Vanar’s importance, if it earns it, would come from making onchain actions feel like background plumbing, not like a negotiation with the network every time you click.

The way Vanar tries to do this starts with being compatible with the Ethereum style environment that most developers already know. That choice is less exciting than inventing a whole new smart contract world, but it is practical. It means developers can bring familiar tools, familiar coding patterns, and familiar wallet support more easily. In the real world, compatibility is not just a technical feature, it is a coordination shortcut. When a chain looks familiar, more people can ship on it sooner, and the chain has a chance to grow an ecosystem before attention moves on.

Vanar also leans into speed, because consumer apps punish slow feedback. In a game, waiting several seconds for a basic action feels broken. In a marketplace, delays create anxiety and support tickets. So the network aims for quick block times and fast confirmation. Again, not glamorous, but it is closer to what normal users expect.

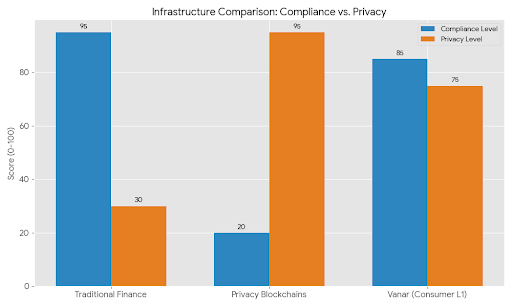

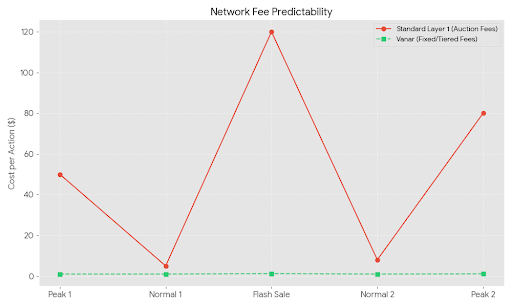

The most distinctive idea in Vanar’s design is the push toward fixed fees priced in dollars. Most chains treat fees like an auction, you pay more when demand rises. That is logical from a market perspective, but it is messy from a product perspective. A developer cannot easily promise a stable experience when costs swing around. Vanar’s approach tries to make fees behave more like a stable price list, where a simple action costs a tiny, consistent amount in dollar terms, and heavier actions cost more in predictable tiers.

If that works well, it changes how people build. A studio can plan budgets. A brand can run a campaign without worrying that the chain will price out its own users during a spike. A marketplace can support many small transactions without turning into a luxury experience on busy days. This is the part where Vanar feels like it is thinking about retention, not just onboarding. Retention is about habits, and habits require reliability.

But this is also where tradeoffs sneak in. To price fees in dollars, the network needs a way to translate dollars into the token used to pay fees. That means some kind of price input system, and some governance around how that system works. In plain terms, Vanar is swapping one kind of uncertainty (auction style fees) for another kind of responsibility (keeping the pricing mechanism honest, accurate, and resilient). If the price input is wrong or manipulated, fixed fees stop being fair. If the mechanism is too centralized, people may worry that fee policy can be changed in ways that benefit insiders. So the design is not automatically better, it is a different set of problems, and the real question becomes whether the team and the community can handle those problems in a transparent way over time.

Tokenomics sits right under all of this, because stable fees are a user experience goal, but validators still need to be paid, builders still need incentives, and the network still needs security. Vanar is powered by the VANRY token, which is used for gas and is also connected to staking and validator rewards. The big picture is that supply is capped at a maximum number, but issuance is spread over many years, meaning there are emissions rather than a hard fixed supply from day one. Many networks do this, because early on they cannot rely on fee revenue alone to pay for security and growth.

The healthy way to think about VANRY is as a fuel token plus a coordination token. It fuels activity on the chain, and it coordinates the incentives of validators, developers, and users. If the chain becomes genuinely useful, then fee activity can start to matter more, and emissions become a smaller part of the story. If the chain struggles to attract steady usage, then emissions become the main economic engine, which can create pressure because people often sell rewards to cover costs. This is not unique to Vanar, it is a structural reality for most young networks.

There is also a separate point that matters for trust. Public token allocation details have not always been perfectly consistent across different documents that people reference. That does not automatically mean anything bad, it can happen when plans evolve, or when different parties describe the same thing in slightly different ways. But it does mean anyone taking the tokenomics seriously should verify the final distribution and circulating supply using the most direct sources available, including official releases and onchain data. If a project wants long term credibility, clarity is not optional, it is part of the product.

The ecosystem side is where Vanar’s strategy becomes more concrete. It is not trying to be a chain that waits for random developers to show up. It is trying to pair infrastructure with consumer facing products and networks. Virtua is one of the main examples people associate with Vanar, and it matters because it represents the kind of repeated user activity the chain wants, collecting, trading, using items in experiences, and moving between marketplaces and environments. VGN is often described as a gaming network layer, a way to connect games and engagement loops to the chain. Whether every part of these visions lands exactly as planned, the logic is clear. Vanar is trying to seed its own demand, not only by convincing developers, but by hosting experiences that already have reasons for people to come back.

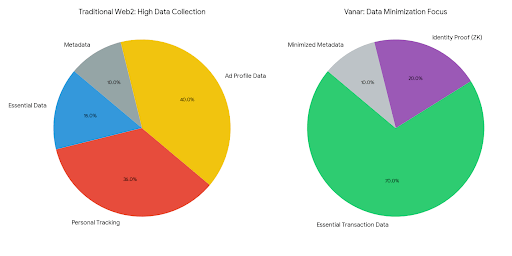

This is where the system level framing helps. Most Web3 projects focus on ownership and speculation. Those are real drivers, but they are not enough for mainstream retention. Mainstream retention comes from meaning and routine. Games keep users through progression, identity, social status, and discovery. Brands keep users through membership and experiences that feel special. Metaverse style spaces keep users through community and content. Vanar is trying to position the chain as the shared ledger that can support those loops without making them fragile.

In that sense, Vanar is attempting to be a coordination layer for consumer economies. It wants to make it easy for a studio to run an in game economy, for a marketplace to handle lots of small trades, for a user to own an item that actually moves with them across experiences, and for fees to stay predictable enough that none of this collapses during busy moments. That is a real problem in Web3. Plenty of chains can process transactions, far fewer make it easy to build something that feels normal to millions of people.

Roadmap direction is harder to pin down without turning this into a list of promises, but the direction feels like two parallel tracks. One track is core chain maturity, stability, developer tooling, validator growth, and the boring reliability work that decides whether builders trust the network. The other track is expanding upward into application layers, including the AI themed parts Vanar talks about, such as memory and reasoning systems, and automation layers meant to support more complex consumer or enterprise workflows.

The honest way to read that is cautiously. AI language can be vague in crypto, and it is easy for any project to sound futuristic. The question is whether these layers become real developer advantages, like easier personalization, safer automation, better user onboarding flows, or better ways to manage identity and permissions, without leaking private data or creating new attack surfaces. If the AI direction becomes practical tooling that helps teams ship and iterate faster, it could be meaningful. If it stays mostly branding, the chain will still live or die on its basic value proposition, predictable fees, speed, and real apps that keep users.

Now for the hard part, challenges and risks, the stuff that matters more than slogans.

A big risk is decentralization and trust. Vanar’s validator model is not framed as fully permissionless from day one. A more curated validator set can help performance and coordination early on, but it also means the chain’s neutrality depends on governance and the integrity of the operators. For consumer apps and brands, that might be acceptable, sometimes they actually want clearer accountability. For other parts of crypto, it can be a red line. If Vanar wants broad credibility, it will need to show a believable path toward a validator set that is not simply controlled by a small group.

Another risk is that fixed fees can create new edge cases. If fees are too low, spam becomes cheap, and the network has to defend itself with other mechanisms. If fees are too high, the user experience breaks, and consumer apps suffer. If the price translation mechanism is controversial, people may argue that fees are being tuned to benefit certain parties. These are not unsolvable problems, but they require steady, transparent operation, especially during volatile market periods.

Another risk is focus and execution. Building a reliable base chain is difficult. Building consumer products is also difficult. Doing both, while also pushing a bigger multi layer story, can stretch a team. The upside is that real consumer products create feedback, they force the chain to improve where it matters. The downside is ecosystem concentration. If a chain’s activity depends too heavily on one or two flagship products, any drop in those products can ripple through the whole network.

There is also the risk of narrative overcrowding. Many chains chase gaming and entertainment. The category is crowded, and partnerships are often temporary. The real moat is not a theme, it is whether developers can ship, users can stay, and the economics can hold up without constant incentives.

So what is Vanar really trying to solve, in one simple sentence. It is trying to make onchain consumer products economically predictable and emotionally frictionless, so users can build habits and communities instead of fighting the mechanics of crypto.

If Vanar succeeds, it will not feel like a big crypto moment. It will feel boring, like something you use without thinking, the way you do not think about cloud servers when you open a music app. That is actually the point. The hardest test will be whether Vanar can keep fees predictable and performance smooth while growing a validator set and a governance culture that people trust. If it can, then it is not just another chain, it is a credible attempt at the missing middle in Web3, the place where products live long enough to matter.